Starting Over With Glazing; Getting the Silica Right

One of the goals for any potter is to reduce variables just enough to end up with pieces that are great to look, functional and aren’t fused to the kiln shelf. At least, that’s my goal. There are many different factors at play starting with clay and ending with the glaze firing. Sandwiched between are several factors that include choosing the right clay body, forming it well, properly drying work, bisque firing to the right temperature, selecting glazes that match the clay, mixing the glazes correctly, properly applying glazes, loading the kiln, firing it well and allowing for cooling. I have probably forgotten a few others. There are many. I had some ideas that I shared in a previous blog post about how to make some modifications to the kiln in order to even out the temperature difference between the top and bottom, but I also needed to look carefully at my glazes and be certain their integrity was unquestionable. The buckets containing my four glazes sat in my unheated studio through about five years of changing seasons and so in addition to not trusting that they were okay, there wasn’t enough left in the buckets to cover any great amount of work. Given I wanted to eliminate as many unwanted variables as possible, it was a good time to get some clean buckets, order some chemicals and start over with freshly mixed glazes.

I start by doing some calculations with the glaze recipes in order to mix up batches of 9,000 grams for each glaze, enough to almost fill a five gallon bucket. I worked up an order for the chemicals I needed and the quantities of each, emailed the order to my supplier and made a day of it by driving to pick up the chemicals as well as some more clay. The eight hour drive down and back to Massachusetts was still cheaper than the shipping charge.

Mixing glazes is like following any recipe as there are two primary things to remember. The first is to use the right ingredients and the second is to make sure the amounts of each are correct. The glazes that I mixed when I was a student at RIT were done in the school’s glaze pantry that was close to the size of a classroom and fully equipped with every possible glaze chemical, an effective exhaust system, two massive stainless steel sinks, cold and hot water, triple beam scales located within arm’s reach no matter where you were working and a glaze pantry assistant who was available to answer every question and see to every need. Contrast that with the set up in my studio today that includes a recycled countertop sitting on sawhorses, thirty or so plastic bags of glaze ingredients tucked into a plastic tote, a hose supplying very cold water, a respirator and a scale that I salvaged from a recycling store. Other than the physical differences in the setup, the process is the same. Look at the recipe, note the name of the ingredient, scoop out an estimate of the amount called for, place it in the pan on the scale, add some or take some away accordingly, dump the chemical not needed back into the plastic bag it came from (this is very important), dump the pan with correct weight of the chemical into the glaze bucket that contains just less than the correct amount of water that will be needed (it’s always easier to add more water later than it is to remove some if there’s too much) and then repeat with the next chemical and so on until all of the chemicals are in the bucket. Each of the glazes that I’m currently using contains about ten different chemicals. Finally, I mix up the batch slowly with an electric drill and paint mixer attachment and finally run the batch through a sieve that will remove any impurities as well as break up chunks. The glaze is fully mixed after two passes through the sieve and the amount of water is tweaked a bit to end up with the correct consistency. I’ve recently added a process to determine the specific gravity of the glaze with respect to water content, but the right consistency for most glazes is about that of heavy cream.

As I was pushing the first glaze through my rotary sieve, I noticed that some of the material was not flowing through the sieve easily or maybe at all. I was pretty sure it was the silica. Every chemical in a glaze is critical, but silica is one of the three main ingredients of clays and glaze materials, along with alumina and ceramic fluxes. It is a glass-former and is the principal ingredient in ceramic glazes. I thought it looked too coarse when I was measuring it out, but figured it was okay, especially since that was what the folks at the ceramic supply company sold me when I asked for silica. It just would not go through the openings in the sieve, despite how long I tried to push it through. In the end, I dumped the material that wouldn’t go through back into the glaze bucket and decided I needed to do some research into whether the silica that I put in the glaze was in fact the right stuff. Isn’t silica, silica? With all of the glaze chemicals added to each bucket and mixed up but not sieved due to the silica clogging up, I had a sinking feeling that I had screwed up. So much for reducing variables.

I contacted the supplier and was put in touch with their glaze expert in the office. I explained the situation. He looked over my recent order of chemicals to see what I was working with. After a few minutes of silence while he looked over my order, he said that it looked like the problem was the silica. Just as I had expected. Our conversation from there went like this. He offered, “Looks like you ordered silica sand. Why did you order that instead of silica oxide? You never put silica sand in glazes. You wanted silica oxide or flint, not silica sand.” I said, “Oh, okay, thanks.” Yup, I screwed up

I tried to remember whether I had a conversation with anyone at the supply company when I placed the order about which silica I wanted, but I couldn’t. Did someone ask if me which silica I wanted, oxide or sand, and I answered sand? Whatever the case, he confirmed what I had feared that I had four buckets of glaze that likely would have to be dumped. In addition to being angry about the possibility that close to 40,000 grams (almost 90 pounds!) of glaze was wasted, I was unsure how I would properly dispose of it. I had wasted some valuable resources of chemicals, time and money and I felt very stupid. Shifting the blame to the folks at the supplier lasted only a few minutes and then the blame came back to me. I emailed the glaze expert at the supply company and asked if I might be able to screen out the silica sand and add some silica oxide thereby salvaging the batches of glaze. He thought that might work, but it could also result, in his words, a huge mess. He suggested that I run plenty of tests before using it on pots. I thanked him for the advice and then closed by telling him that I was just returning to ceramics after having been away from if for about 45 years. Maybe, I wrote, I had waited too long. After not getting a response back from him like, don’t worry about the silica mistake, everybody does that or; hey, no worries, you’re never too old or; maybe something like, good for you!, I got nothing. Maybe I had waited too long. It had been a long time since taking glaze chemistry in college. Maybe too long.

In September of 1971, I started my first year as a ceramics major at the School for American Craftsmen (since renamed the School for American Crafts to reflect that women can also work at crafts) at Rochester Institute of Technology in Rochester, New York. There were fewer than ten of us admitted to the program as freshmen that year and along with about the same number of students in each of the other three classes and a handful of graduate student, we were the ceramics program. I was 18 years old and eager to learn. Coming from Vermont and a small town with a small high school, we didn’t have an Art program until I was a junior and even them, ceramics was not part of the curriculum. I learned to make pots from a man in our community who was generous enough to welcome me as his student every afternoon and on weekends in exchange for me helping him with his work and with jobs around the studio. My first class at RIT on my first day of college was glaze chemistry. The class met in a small conference room that had tables and chalkboard and was located just inside the main entrance to the ceramics department. The tables were big enough for the eight of us and our professor, Hobart Cowles, to sit around with space for our notebooks and books and several ashtrays. Hobart was probably in his late forties then, slim, balding, trimmed grey mustache, glasses with a serious demeanor, very serious. In those days, smoking cigarettes was a normal activity not only in college buildings, but in classes and many of us, including Hobart, smoked during class. About two minutes into every session of glaze chemistry, the room was full of smoke and stayed that way until someone opened the door or the class ended. I didn’t see it then (I quit smoking three years later), but how inconsiderate and irresponsible could we possibly have been, but that’s just the way it was.

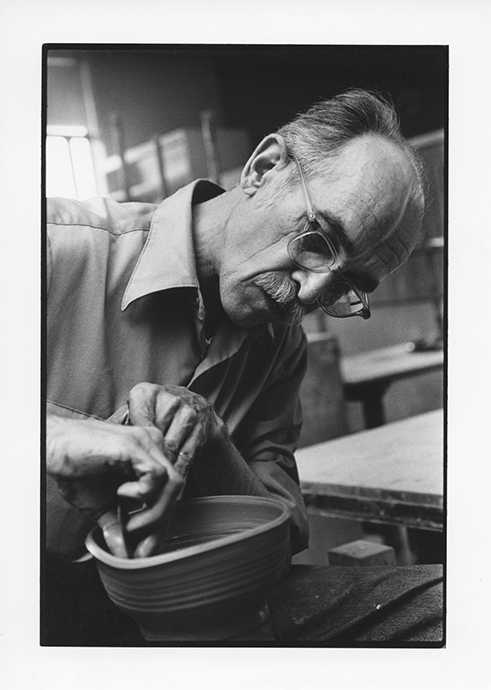

Hobart Cowles at work (Photo courtesy of RIT Archive Collections)

Hobart was the technical expert and along with Bob Schmitz, the design and kiln expert, they formed the ceramics teaching team. Hobart’s work was both hand built and wheel formed and included boxes, lidded jars and sculpture decorated with glazes he designed, calculated, tested and perfected. He didn’t talk much about his work, instead he focused on teaching glaze chemistry and making all of us aspiring potters, glaze chemists. Searching for his glazes now online, they are everywhere. I appreciate his work more now than I did back then. Each class started with Hobart clearing his throat and then very deliberately transitioning to some aspect of designing glazes that included; balancing chemical equations, demonstrating the correct use of a jewelers eyepiece for inspecting glaze surfaces, pulling out his slide rule to run a calculation (as this was before the hand held electronic calculator) or sharing some examples of glazes he had perfected over the years. When a question was posed, he would listen carefully, sit quietly and reflect for a bit, take a pull on his cigarette and then answer, slowly. I wish I had paid closer attention to Hobart and the glaze chemistry class, but I didn’t. Despite that, I did learn some basic chemistry, created some glaze recipes, tested them and corrected them to limit the faults to a minimum. My memory is just foggy enough to recall whether there was any focus in his classes on silica sand versus silica oxide. In the end, as it turned out, we learned from more seasoned undergrad and graduate students that glaze chemistry was important, but not nearly as critical as having a network of potters to share recipes with that had been tried and tested. The internet, where access to thousands of glazes in now available, was not even imagined by us in that class in 1971.

There was a lot about RIT that I loved, even though I left after two years and returned to Vermont. It was an amazing time to be involved in making pottery or any kind of craft work as we seemed to have the common goal of wanting to hold tightly to the traditions from yesterday rather than what we were facing today and even more concerning, tomorrow. There was a purity and wholesomeness to making things that some of us could see starting to go away. When the draft lottery for the Vietnam War took place in February 1972, several of us who were eligible and others who were interested huddled around a radio in the middle of the studio to hear when our birth dates were drawn. There were 366 possibilities. The earlier your birth date was drawn the more likely you would be drafted and spend some time in the service and likely in Vietnam. Our freshman class was the first class entering college not to have the benefit of a college deferment as those who entered before us had. Needless to say, February 24th was drawn on the 261st round and so I was likely not to be drafted. Luckily, soon after, President Nixon reduced reliance on the draft and a year later, decided to rely solely on a volunteer military service. The war ended in 1975 and there hasn’t been a military draft since.

I had a sense back then that my work making pots and the all the other things that I was immersed in was my contribution to returning to something from the past, reject the direction the country was heading and slow things down. These were the early years of several big movements that drew attention to the environment, civil rights, women’s rights, economic inequality and the peace movement. Our country was committed to fighting a war that most of us didn’t support and for the first time in our lives, it was taking place in real time on our televisions at night. Every night the latest tally of deaths was reported for both the United States and North Vietnam. I became friends with several students who enrolled at RIT after serving in Vietnam. All of them showed some signs of the impact that the war had on them. The initials, PTSD, were not part of our vocabulary then, but it was obvious that something bad had happened to them. In addition to obvious emotional impact, some had more visible signs such as missing limbs. I remember getting to know one guy who was in a drawing class with me who had just returned from a year in rehab where he learned how to walk on two prosthetic legs. Although I had genuine appreciation for all he had experienced and sacrificed, knowing what he had gone through and how it changed his life forever hit me very hard then and stuck with me over the years since. It was also when I understood the paradox of supporting the soldier, but not the war. I found sitting at a potter’s wheel and throwing a pot that someone would be using to eat food from made sense and it felt right for me as much then as it does today.

Photo from 1972 while attending RIT

I returned to thinking more about Hobart Cowles as I prepared to remix the glazes, this time with the right silica, and realized I knew little about him before, during and after he was my teacher. I found the excerpt below from a piece written about him by his wife after he died in 1980.

Hobart Cowles was born in Madison, Ohio early in the roaring twenties. Madison is in northeastern Ohio, about twenty miles west of Ashtabula. Born in a predominantly farming community, he became acquainted with clay early in life. His early experiments with clay were conducted in the "crick", baked in the sun and eventually were returned to the "crick." Providentially it was some twenty years before he learned that firing his works would make them somewhat more permanent if not necessarily more noteworthy.

His contact and investigations of the material continued in the forties on golf courses in Ohio and on location in Texas, Wisconsin, England, France, Belgium, Luxembourg and Germany, with the 76th Infantry Division. In the latter role he came literally face to face with the medium on numerous occasions. Finding study in Europe at that time somewhat difficult, he returned to his homeland and the then quiet and peaceful college campus to continue his investigations into the subject of clay. Georgia seemed to be a promising locale. In reviewing his course of study, his advisor suggested that a course in "ceramics" might be taken during an open period in his schedule. After asking what "ceramics" meant, he elected to take the course and thus he slipped into a B.F.A. in ceramics in 1949. Returning to his native Ohio, he earned a M.A. in ceramics from the Ohio State University in 1950.

In 1951 he was permitted to join the faculty of the School for American Craftsmen, presumable because he was an American. Due to the excellence of his fellow faculty and a steady stream of remarkably talented students, he has been able to retain this position.

Despite the discriminating and untiring efforts of juries and selection committees, his work has been shown in the Syracuse Ceramic National, Syracuse Regional, Rochester Finger Lakes Exhibition, the Brussels World's Fair, the New York State Exposition, the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, the York State Craft Fair and several others which it might be best not to mention.

The most extensive collections of his work are owned by his mother, his wife, Barbara, and The Three Crowns in Pittsford, New York. The latter, being a retail outlet, is attempting to reduce the size of its collection. Although there is a generous lack of appreciation for his work in this country, it is recognized in Turkey, Korea, Viet Nam, the Philippines and Japan; at least by former students from those countries. He has executed works on commission for several churches and individuals in the Rochester area indicating the benevolent and forgiving attitude of such individuals and institutions. Another benevolent and forgiving group in Fishers, New York has for some years sponsored and encouraged him in his work: his wife, Barbara, and his children Judy, Becky, Jon, Meg and Dave.

-excert from Hobart Cowles: A Retrospective... by Barbara Cowles

Hobart Cowles Obituary from the American Crafts Council